On August 21, Nikki Bhati was allegedly set ablaze by her husband, Vipin Bhati. Her family stated that they gifted her in-laws a Scorpio, a motorcycle, and gold during the wedding in 2016. But there was no satiating the demand, and they were later presented with a fresh demand of Rs 36 lakh and a luxury car. The 26-year-old woman was found with severe burn injuries at her in-laws’ home on August 21 and later died en route to a Delhi hospital. Nikki’s death has sparked renewed outrage surrounding the concern of dowry deaths and the give-and-take of dowry altogether.

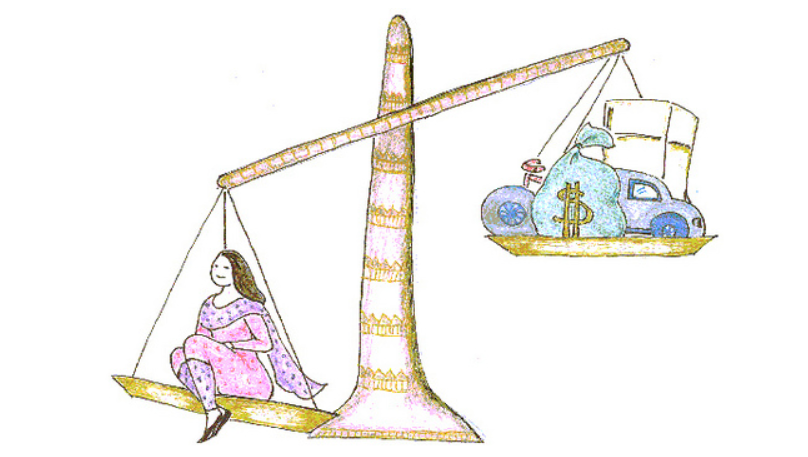

Nikki Bhati’s death has prompted public outcry and renewed debate over India’s dowry-related violence. Reported dowry deaths, however, represent only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the violence married women face within their households. According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), 35,493 brides died in India between 2017 and 2022, which averages to nearly 20 deaths a day over dowry demands. In this period, Uttar Pradesh recorded the highest number of dowry deaths, followed by Bihar and Jharkhand. Section 80 of Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) 2023 states that the term “dowry death” is applicable when a woman dies due to bodily injury or harm up to seven years after her marriage, and it is shown that she was subjected to cruelty and/or harassment by either her husband or his parents and/or extended family. A 2010 book named Human Development in India: Challenges for a Society in Transition, covers the findings of the 2004-05 round of the India Human Development Survey (IHDS), which shows that the average wedding spending for a bride’s family was 1.5 times more than the bridegroom’s family. Behind these numbers are real women whose lives are cut short by relentless demands. Recent cases across states reveal how dowry harassment continues to escalate into brutal violence and deaths.

Sangeeta, a mother of two and a ten-year married woman, was discovered dead on June 14 in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, after allegedly being severely beaten and tortured with a hot iron on every part of her body, including her genitals. According to the woman’s family, she was often tormented by her husband and in-laws since they had not received the buffalo and bullet motorbike they had demanded as dowry. A young Chandigarh bride killed herself last July following what her family said was constant dowry harassment. Later that month, despite receiving a ₹70 lakh Volvo and 100 sovereigns of gold as dowry, another bride committed suicide within two months of marriage as a result of constant pressure relating to the dowry.

These recent tragedies are not isolated incidents, but they stem from a longer history of dowry-linked violence in India. To understand why the practice persists so deeply, it is important to trace how dowry itself evolved. Dowry did not originate as a weapon of social violence; instead, it was known as ‘stridhan’ or a woman’s wealth, comprising jewellery, gold coins, and cattle, which was parted with by the bride’s family to accompany her in her married life, serving as a source of financial independence. By the medieval era, as caste hierarchies deepened, marriages became negotiations of status, dowries evolved into grand transactions, and the bride’s worth was calculated in terms of the wealth she was accompanied by. One of the earliest well-documented dowry killings occurred on 15 May 1979 in Model Town, North Delhi. Tarvinder Kaur, a Sikh bride, was attacked in her home by her mother-in-law, who doused her with kerosene, and her sister-in-law set her on fire.

Today, the concept of dowry has evolved, and no longer fits the traditional framework of “give-and-take.” The bride’s family is expected to pay for the extravagant venues, luxurious food, stay, and whatnot. The honeymoon abroad and the luxury apartments “gifted” by the bride’s family all stem from the same social evil. Far from being abolished, the dowry system has been repackaged as status-driven consumption and reinforced by a consumerist mindset.

The debate over dowry laws has sharpened with the ongoing Tellmy Jolly v. Union of India case, which includes a petition before the Supreme Court that questions whether parents who give dowry under coercion should be punished alongside those who demand it. Tellmy argues that, in punishing givers, the law criminalises the very people that it is supposed to shield. While the case highlights the criminalisation of victims, the Kerala government, in response to related proceedings, has recently informed the High Court that it has launched a dedicated portal for dowry complaints and is drafting a standard operating procedure for handling such cases. With the constantly rising dowry-related harassment cases rising every day in India, concerned citizens are bound to ask, “Will this portal be effective?”

On one hand, a digital portal will make filing easier for victims (or their families), as they don’t need to go to police stations, which are often intimidating or dismissive. However, rural families may lack either digital access or literacy to access this portal. A digital approach to reporting issues such as dowry deaths and harassment can be effective, but only if it is paired with awareness campaigns, trained officers, and prompt action on complaints.

While initiatives like Kerala’s dowry complaint web and the Tellmy Jolly petition demonstrate efforts to change the system, they also highlight the limitations of both digital and legal solutions. The continued prevalence of dowry-related violence serves as a reminder that the issue is much more complex than access to technology or the legal system, despite every new precaution that is put in place. Nikki Bhati’s case sits within a long continuum of dowry-linked violence that continues to surface across India, despite decades of legal prohibition. From the earliest recorded killings to recent tragedies, the pattern has remained disturbingly consistent, where demands escalate, families concede or resist, and women end up bearing the consequences. The persistence of such deaths shows how resistant the system is to reform. Dowry remains a deeply entrenched practice which has been consistently reshaped over time but never dismantled, leaving a legacy of inequality that continues to undermine marriage and justice alike.

Leave a Reply